Writing this book was very much a case of piecing together scraps of information that I uncovered over many years and subsequently added to my own memories. Sometimes these were letters and photographs, sometimes accounts by others, and together they all helped build a picture of the past. Ephemera – diaries, letters, photographs, notes, sketches, bills – are the physical objects that add solidity to biography and memoir; you can’t make them up. How a writer or curator uses them to tell the story is another question.

Writing this book was very much a case of piecing together scraps of information that I uncovered over many years and subsequently added to my own memories. Sometimes these were letters and photographs, sometimes accounts by others, and together they all helped build a picture of the past. Ephemera – diaries, letters, photographs, notes, sketches, bills – are the physical objects that add solidity to biography and memoir; you can’t make them up. How a writer or curator uses them to tell the story is another question.

In researching the House of Fiction I was fortunate in that I tend to keep all sorts of apparently useless things, and also that most of the correspondence was by letter rather than email and text message as it is today, so I had letters from my father, from Elizabeth, from my mother and from my aunt, Laura. My diaries, which might have proved very useful had I kept up the entries beyond the end of January every year, were of very limited value. However, amongst the muddle of an old filing cabinet and boxes in the attic I found relevant letters, family albums and postcards. In my parents’ house I found, after my stepfather’s death, some of my mother’s diaries, but no letters from my father to her (I suspect these were destroyed). Laura was a tremendously valuable source of material because she had kept stuff – lots of it, that she then handed on to me, and much of it was relevant to this story.

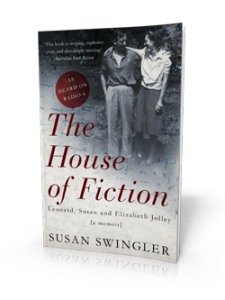

Having worked both as a photographer and a researcher and curator, I was very keen to include photographs in the book. Some were drawn from family albums, but the most startling I found after my mother’s death, wedged at the back of a drawer. There were no prints, just wallets of negatives. I believe that she threw away the prints but couldn’t bring herself to destroy the negatives.

Family ‘archives’, such as most of us have, are rarely ordered and categorised, but official archives are, and I was again fortunate that Elizabeth and Leonard had kept all their correspondence, or at least, all that passed between them, and Elizabeth donated this correspondence to the State Library of New South Wales. I was allowed access to some of these letters, but was not permitted to quote from them or reproduce them and so unfortunately none appear here. There are also Elizabeth’s and Leonard’s diaries, but they will remain embargoed for years to come. So the picture is not yet complete.

No matter how much ‘evidence’ of this nature appears – and more has turned up since the book was first published in 2012 – and yet more will appear once the Jolleys’ diaries are available to the public – nobody will be able to say, ‘this is the definitive story’ because so much depends on interpretation. For example, while searching for more photographs and letters for an Australian television programme about this story, I came across three letters from my father to me that I had missed when writing the book. These are shown below for the first time. For me they ‘prove’ my father was thinking about me when he sailed for Australia, and they provide a welcome contrast to some of the letters he wrote to me when I was an adult. It is interesting to consider how the scraps of paper that survive, either by judicious editing or by chance, can shape the way we see the past.

Letters

Over the course of forty years, I corresponded with my father Leonard, and later with his wife Elizabeth Jolley, without ever seeing them. Little did I know that for the first seventeen years after my father left me and my mother, Elizabeth was also corresponding with my father’s family in such a way as to lead them to believe that my mother and I were with Leonard, first in Scotland, and later in Australia. Here are some of those letters, along with letters from my mother, Joyce, and my aunt, Laura, whose ‘account’ of events she offered me in note form.

Photographs

Photographs are used as evidence in court cases, they also provide us with evidence of our own pasts. Stuck into family albums, dated and labeled, they provide a picture of a world that is gone – great-grandparents who died before we were born, houses we have only a dim memory of, landscapes and beaches bathed in the sunshine of nostalgia. Susan, with the help of her family, uncovered many such old photos. But she also found pictures tucked away at the back of a drawer, of a time that her mother undoubtedly would rather have forgotten, of times when she, Leonard and Elizabeth photographed each other with the two babies, Susan and Sarah. The photos here show Leonard, Joyce and Elizabeth with the two newborn babies in Joyce and Leonard’s home in Birmingham in 1946 and others that were taken in the same garden two years later, when the children were toddlers. The two schools, in England and France where Joyce and Susan lived are also shown, along with Joyce’s family on the beach at Deal in Kent the summer Leonard left.